Here's a headline you might come across while reading the news:

or maybe one like this:

You've been exposed to the news often enough that I bet you have some vague sense of what these things mean. "S&P 500 falls" is probably a bad thing. The Fed is going to decide... something that's probably important? "Market turmoil" sounds bad. And why is Italy borrowing money anyway?

In other words, when you open the news, and a financial story comes up, do your eyes glaze over a bit? Do you think to yourself, I'm a smart person, why doesn't any of this make sense?

Or maybe it hits a little closer to home. Maybe you think about people who work in finance and say to yourself, I have no idea what they do. Why are they so rich, and why does the news make it seem like the world revolves around them?

I have good news for you: finance is not that complicated. We can build up some basic mental models of finance in one sitting, starting from the absolute basics and working our way up to a simple model of the economy.

By the time you're done reading this, you should have a working idea of what a stock or bond even is, why it does (or doesn't) matter when their prices go up or down, how it connects to our everyday lives, and why it is that the governments always seems to be getting involved.

I gave a talk a few years ago on a similar topic, but pitched at people who were trying to understand enough finance to handle their own personal investments (or to know enough to pay someone to help them). It was called Financial Self-Care in a Capitalist Society. If there’s interest in a personal-finance-tinged version of this same write up, drop me a line and I’ll pull it together.

Why learn about finance?

In short, you live in a world shaped by finance, for better and worse.

At the moment I'm writing this, the stock market is tanking, and we're at risk of a recession. Even if you don't know what all of those words mean, or how they're related, nevertheless they will have an effect on your ability to get a job, rent an apartment, buy a car, or pay student loans. We live in a society whose basic building blocks, like food, shelter, and education, are deeply intertwined with local and global financial markets and with how those markets are regulated. Meanwhile, most of it goes over our heads.

I graduated college directly into the 2008 financial crisis and its aftermath, and as much as I tried at the time, I couldn't really grasp the mechanics of what had happened. A few years later, I was running a small consulting company, and was in the terrifying position of having most of my money tied up in a small business.

At that point I realized I had some gaps to fill in my understanding of finance, both for the sake of the business and for my own ability to get what was happening around me in the broader world. I had taken some economics classes in college, but none of that seemed to really help.

So I decided to educate myself. I subscribed to the Financial Times and the Economist, looking up all of the terms that confused me. I took several online MBA courses in corporate finance and accounting. I read a number of books on corporate finance, personal finance, and the history of capitalism. I read Matt Levine's Money Stuff religiously.

Eventually, I wound down the consultancy and I took a job at a fast-growth startup. In my role heading up the Data team, I regularly interacted with the Finance team. I picked their collective brain when I could. Part of my job was to talk about finance with the Data team every quarter so they knew how the company was doing. I got a lot of practice explaining financial concepts to people with no background in this field.

All of this is to say: I'm not a credentialed finance expert, don't take me for one. All the errors are mine. I just find this stuff fascinating and important. I've never worked in finance, and I've got no professional qualifications. But as an outsider, and someone who thinks these things are, for better or worse, pretty critical, I think I can explain how this world works well enough for you to get by.

Prelude: a simple model of renting an apartment

Before we dive into models of finance, let's start with a model of something that you are probably already quite familiar with: renting an apartment.

To explain finance, I'm going to primarily rely on something called a sequence diagram. A sequence diagram is a tool developed by computer programmers to make complicated processes easier to understand.

Let's look at a sequence diagram representing how someone rents an apartment, starting when a renter gets the listing for the apartment. Each column is an actor; in this case, our actors are a renter and a landlord.

In our first model, we start with a renter sending their deposit to their landlord. Then they repeatedly pay their rent, until eventually they stop and they get their deposit back (assuming they don’t stop paying and get evicted, of course).

This tells us something about the process of renting, but it's still pretty simplified. Let's take a moment to make a slightly more nuanced model of how renting an apartment works.

Take a closer look at our better model. Landlords send a listing to the renter, whether through a broker or by posting it on a website. The renter, after paying their deposit, gets keys to the apartment, which they return at the end of their rental contract before they can get their deposit back.

You might also notice that the lines for rent and deposit are now dotted. That’s because they’re not actually guaranteed. Someone could stop paying, in which case they still owe the keys back to their landlord but they’re not likely to get their deposit.

Obviously there's still a lot missing here; nothing about how a potential renter finds an apartment in the first place, or details on signing a lease. Nothing about the details of the rental contract, or what happens if the renter stops paying. No details about the view or whether or not the apartment has mice. These things are all important to an individual instance of renting an apartment, but not relevant to understanding the big picture.

The point of a model is to give us that big picture, a simplified view, and it's up to us to decide how simplified that model is. We're going to be doing something similar when it comes to models of finance and of financial transactions, starting with a very simple model and gradually working our way up to something with enough nuance to be useful, hopefully without ever getting too much in the weeds.

Who does what?

Our very first model of finance is that investors give money to corporations, and maybe they get more money back later to reward them for giving money up front.

In a moment we'll get more clear about what "maybe" and "more" actually means. But for now, here's out very first model of finance:

As before, time goes goes from the top to the bottom. We have two actors: an investor and a corporation. The investor give money to the corporation, making an investment, because they hope to get back more money in the future. Later, maybe the corporation gives the investor more money. To illustrate that the money later is not guaranteed, we've used a dotted line, just like with the rent.

Let's start with the "maybe" part. Some investments have more risk than others. The more risk, the worse chance that the investor gets all of their money back. All else equal, the investor would like lower risk.

To reward the investor for parting with their money (and taking on the risk that they may not get paid back) the corporation intends to give the investor more money in the future than they were given initially. The money that they get back is called return. The higher the return, the better for the investor.

Ideally for the investor, risk is low and return is high. This can't happen, for reasons we will explore in a bit. If it does happen, there is good reason to think it'll be a fluke that won't happen again. There are no consistently low risk, high return investments.

However the opposite can certainly happen: high risk and low return investments happens all the time. That's just called being a bad investment.

Let's make our first improvement to the model. Before any money changes hands, we should be aware that there's a government setting the ground rules in any financial transaction.

Governments define what a corporation is and what kinds of investments are legal. They decide what happens if a corporation can no longer pay their bills. Governments set the rules around contracts, which will become relevant in our next model, including what types of contracts are legal and how they are enforced. They also set some basic rules around money itself, including tax rates and the amount of money that is printed or taken out of circulation each year.

Besides setting the rules, governments are crucial participants in financial transactions too. They are some of the most important participants out there.

Let's make it clear that governments are both setting rules and participating in financial transactions:

Already we have a model that captures a lot of the essential nature of finance. Investors give money to corporations and governments. Investors want a high return, and they want it as low risk as it can be, but those things are in tension.

Successfully navigating risk and reward for both parties in this exchange is the core activity of finance.

Contracts

Let's make our model clearer by adding in a very fundamental piece of the puzzle: contracts. When an investor gives money to a government or corporation, they actually get a legal document back that explains how, and under what circumstances, they're going to be paid back.

The people working at a corporation or in a government who create these contracts are known as the sell side. They are the ones who are creating a contract to be sold to the investor as an investment. Their job is to figure out the terms of the contract and what price they would accept for it. They create a prospectus that explains what they're selling. In the United States, they're legally required to explain the risks involved. Prior to the Great Depression, there were no real rules here, and plenty of companies sold contracts with flimsy information or outright lies.

The investor who decides whether or not to buy the contract is known as the buy side. They have to figure out what price they would be willing to offer to buy the contract. If there is no price that both are happy with, no money changes hands and the deal doesn't get done.

In diagram form, highlighting the new information in green:

The two basic types of contracts that a corporation or government can sell are bonds and stock. Let's look at each in turn.

Bonds

Though the stock market gets most of the attention and news coverage, arguably the bond market is the one that is actually important to the day-to-day functioning of the world. Bonds make up a larger fraction of investment than stocks, but because they can require a little more explanation they get less coverage. Let’s fix that.

A bond is a contract to pay back an investor in the future, plus some additional money each year. The additional amount is called the coupon. The money that an investor gives to a corporation or government, and hope to get back at the end, is called the principal. Whenever someone talks about government or corporate debt, what they mean are bonds that a corporation or government have sold to investors.

Again we’ll highlight the new arrows relating to the new terms in green, in this case coupon and principal:

Corporations often issue bonds when they want to spend a lot of money on something now, like opening up a big new factory, and they don't have the money on hand to pay for that investment right away. They expect the factory will make them money once it’s built, and they can use that money to pay back the bond.

When they sell the bond to an investor, they get money immediately (i.e. the money they’ll use to build the factory), and they are (hopefully) able to pay it back later to the investor, who is known as the bondholder.

For example, a corporation might offer the following bond:

- The bond costs $1000 (the principal)

- They will pay an investor who holds the bond $50 per year, for five years (the coupon)

- At the end of 10 years, they will pay back the $1000 to the investor (paying back the principal)

This bond has a 5% coupon. The investor gets 5% back of the money they put in each year, plus they get the money they put in as principal back at the end. Assuming the corporation continues to make money, they will pay the coupon every year, which the investor has to pay taxes on like they had earned it as income.

Hopefully for the corporation, they used the initial money wisely, and they earn more money now than they did before, enough to pay the coupon and then pay back the principal in full.

If the corporation couldn't pay its coupon, or repay the principal at the end of the life of the bond, they would default on their payments. This is a big deal. Often when a bond is in default, the corporation will then declare bankruptcy.

After declaring bankruptcy, the judge might let the corporation decide to restructure their bonds to pay back, say, only $400 of the original $1000. In other words, to change the terms of the deal. At that point, they might also be forced to sell some things (like a factory) to raise money. In the event of a bankruptcy, bondholders are typically paid back ahead of the owners of the business, meaning they have less at risk than an owner does, but not necessarily that they’ll get back 100% of the principal they put in to start.

Now instead of the expected 5% return, the investor put in $1000, and only got back $500, for a 50% loss. Not great!

In general, when a company goes bankrupt, bond holders get paid out after employees and vendors are paid, and after back taxes, but before any owners get their money back. The riskier the bond, the bigger coupon needs to be to justify the risk.

Independent companies called credit agencies (like Moody's, S&P, and Fitch) are paid to assess the risk that a company will default on a bond. They assign each bond a credit rating to help the Investor decide whether or not the coupon is worth the risk.

These days, typical corporate bonds for a highly creditworthy corporation have a coupon somewhere between 2.5% and 5%.

High-risk corporate bonds, from companies that are at risk of going under, often have a coupon of anywhere from 5 to 15%. The bonds are known as junk bonds, which are high risk and need to offer a large coupon to make the risk palatable.

Government bonds

Governments also issue bonds. Governments use debt a lot. For example, if a city wants to build a new bridge, they might issue a bond with a 30-year term to fund it, instead of temporarily raising taxes significantly and potentially harming individuals or businesses who didn’t plan to get an extra large tax bill.

Similarly to a corporation, a government hopes that it can use the bond money wisely. Their investments, if done well, should cause more people to live and work and pay taxes to the government over the long term. Most large infrastructure projects in the United States these days are funded by bonds.

When it needs to, the government can use the fact that it controls the rules to make their bonds more appealing with tax breaks.

New York City, for example, is able to offer bonds to fund construction on bridges and tunnels at a coupon rate of only about 1.8% per year, meaning that $1000 of investment only gets $18 annually [1]. That doesn’t seem like much money, but for New York City residents, these $18 are tax free at the city, state, and federal level. Combined with their low risk, these tax benefits make the bond attractive to investors, even though the coupon is low.

Back in the 1970s, New York City was at high risk of default. Its bonds went for 9%, comparable to a junk bond![2] New York City never actually defaulted, and from the 1980s through the 2000s its credit rating gradually improved to where it is today.

Sovereign bonds (and especially U.S. Government bonds)

Besides cities and states, countries issue bonds all the time. When a country issues a bond, it's known as a sovereign bond, because it's being issued by a sovereign country, meaning a country which controls its own territory and laws.

Most sovereign bonds are issued by countries to make up for a shortfall between what they want to spend and what they take in taxes. The theory is that they can have lower taxes in the short run, which makes it easier for individuals and businesses to save and spend money, and make up for the difference with debt that it will pay back with growth and future taxes.

Since the 19th century, sovereign countries have tended to put the authority for raising that debt into the hands of central banks, like the Federal Reserve (also known as the Fed), which is the central bank of the United States, the Bank of England, the Bank of Italy, the Central Bank of Iceland, and so on. Every country is different, but in general these institutions are expected to be independent of their country’s main political processes, and they are often connected to large, private banks who can supply the human expertise to run them.

The most important kind of government bond in the world are U.S. Treasury bonds. They are issued by the US Federal Government to fund its operations beyond what it collects in tax revenue.

Because it was victorious in World War II, and at the peak of its influence in the following twenty years, the United States was able to put the dollar at the center of the global financial system. To take one example, almost every oil sale in the world uses dollars, even when neither country in the transaction uses dollars locally. This is one reason that businesses and governments all over the world have copious amounts of U.S. dollars on hand, even when their country doesn’t use dollars. These businesses and governments want to put them someplace safe. There is no such thing as a million (or billion) dollar insured bank account, so the safest thing is U.S. Treasury bonds.

And because the United States has never defaulted on its debt, its short-term bonds (called Treasury Bills or T-Bills for short) are considered "risk free." They're risk free in the following sense: whatever coupon they are paying is taken to be the lowest coupon that anyone can get away with. They are the floor on the whole global financial system.

T-Bills are of course not totally risk free, since the U.S. could default on its debt, but that is considered a low enough chance in practice that they are treated as zero risk. Because the U.S. The U.S. Treasury, since it is also charged with printing physical money, is capable of paying T-Bill coupon payments by, in essence, printing money.

The growth rates of everything else in the global financial system is considered relative to US Treasury bonds. After all, if you can get your money back plus 1% interest with perfect safety by buying T-Bills, someone needs to offer you higher return to compensate you for the greater risk. If the coupon on T-Bills goes up, every other investment needs to be higher return than them, or else nobody will buy it. If T-Bills are available with a 5% coupon (as they were in 2008), or even at a 14% coupon (as they were in 1981), even highly rated corporate bonds will need to offer above that kind of return in order to be worth the additional risk. If they can’t afford to do that, they won’t be able to find someone to invest in their bond, and the corporations and governments will have to deal with not being able to issue any new bonds.

It’s worth pointing out that, since U.S. treasuries are, in fact, globally bought, this means that when the rate for T-Bills shoots up, it dries up investment around the world. Anyone who can’t afford to compete with the U.S. Treasury, who can, in effect, print money to pay their coupon payments, is out of luck.

What does the United States specifically do with this risk-free money that individuals, corporations, and governments around the world are lending it for a pittance? A lot of it goes to fund the military, some of it goes to paying down older debt. Mostly it keeps our taxes low, which encourages investment.

One thing it doesn't do is fund our safety net; Social Security is actually the largest purchaser of U.S. Treasury Bonds, with Medicare up there as well.[3] They use U.S. Treasury Bonds as a safe place to park some of the retirement savings of hundreds of millions of Americans.

Corporations and ownership

We've covered bonds, one of the two types of contracts that an investor can buy in our model. Now let's turn our attention to stocks, which globally a little less money than stocks. Governments don't offer stock, only corporations do. They're a different kind of contract that an investor can buy.

To understand stock, we need to take a little detour into how a corporation actually works.

A corporation is a legal entity, meaning that it only exists because of a legal system that grants it existence. Legally, a corporation can enter into contracts, and buy and sell things. It can own property, just like a person can.

Every country is slightly different in what exactly these legal rules are. Rules are different within states in the U.S. too. For historical reasons, most major U.S. corporations are legally based in Delaware, even if their headquarters is usually elsewhere. Delaware has business-friendly laws and special courts that know how to quickly resolve disputes between businesses.

A corporation has one or more owners, also known as shareholders, who each own some percentage of the company. For example, one person could own 20%, and ten people could own 8% each:

Under the American model, each owner has two fundamental rights:

- Right to decide who runs the corporation

- Right to profit taken out of the corporation

Crucially, these rights are generally proportional to ownership. That is, if you own 20% of the corporation, you get 20% say in who runs it (by voting for members of the Board of Directors, who appoint the Chief Executive Officer to run the company), and 20% of he profit that comes out of it.

This model is basically the same in most of North America and Western Europe... with the notable exception of Germany and Sweden. In these countries, big worker strikes in the middle of the twentieth century enshrined the right of employees to have a say in how the largest companies are governed. These countries provide votes, up to but quite 50% of the voting power, to employees. The rest of the votes come from shareholders, just like with American companies.

Stock

A corporation takes money from an investor and gives them one share of stock. Each share, that is, each individual contract, entitles the shareholder to ownership in a (very small) part of the corporation. Corporations sell these shares to raise money, just like they did with bonds, but instead of needing to pay a coupon every few months, they are relying on future profits to reward investors.

How small is each share in a company? A typical company has between 100 million and 10 billion shares. This means that buying a single share entitles the investor to somewhere between $0.01 and $0.0001 on each million dollars of profit that is taken from the company. That profit per share is known as the dividend. Investors buy stocks because of the future possibilities of dividends.

Just like with a bond, legally the corporation has to prepare a (these days usually digital) prospectus to explain what they're selling and what the risks are.

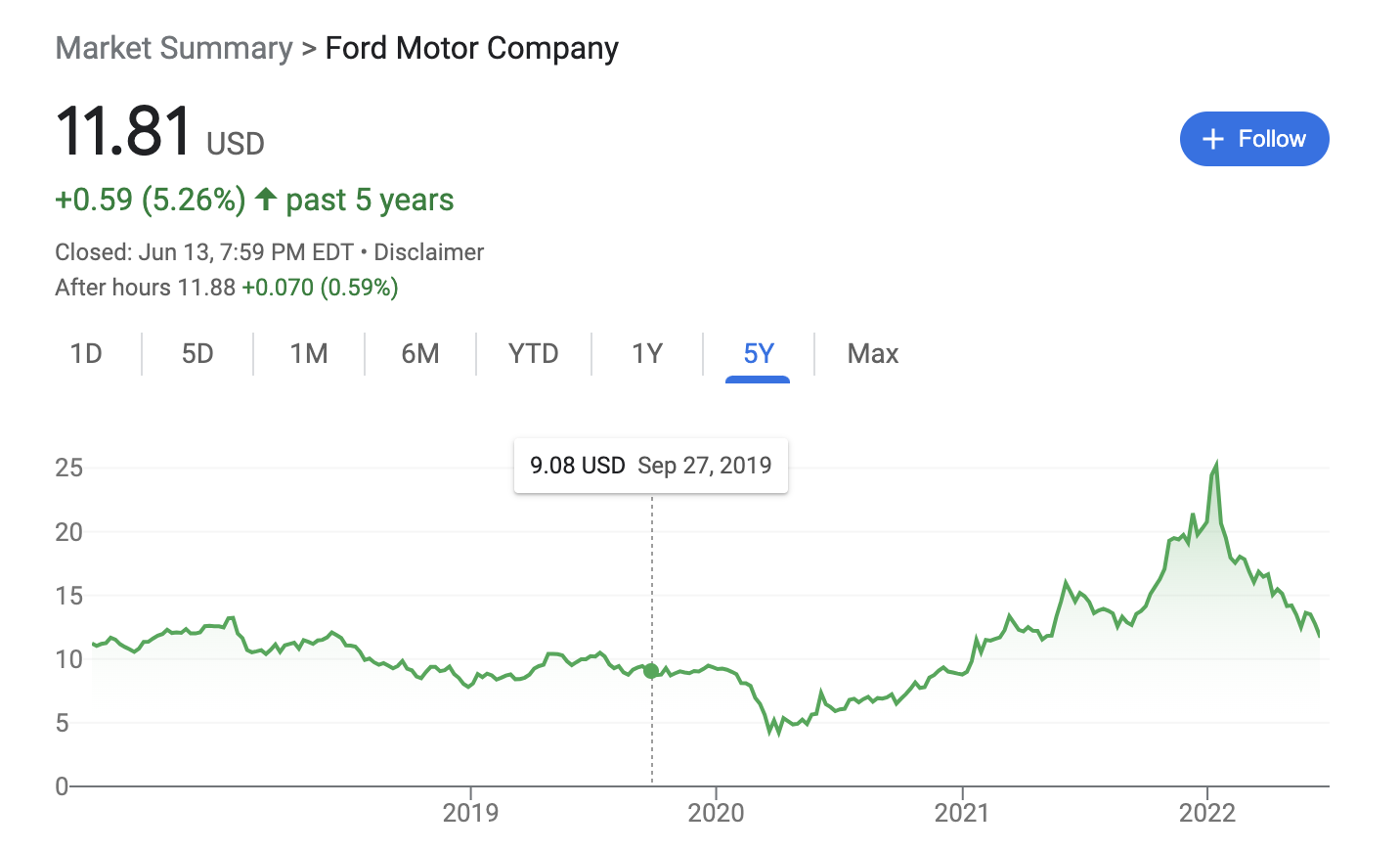

Consider Ford Motor Company. In 2019, Ford had 4 billion shares outstanding, and they voted to provide each share with $0.60 in dividends. In total, it took $2.4 billion dollars of its profit and returned it to its shareholders.

Adding additional investors

Now that we've covered the idea of an investor going to a corporation or a government, and giving money in exchange for a stock or bond, we can add the final really critical step: other investors.

Investor #1 can sell their stock or bond to investor #2, and with that sale goes all of the rights that investor #1 had to start with. Stocks and bonds aren't issued with the name of anyone in particular; the owner of the stock or bond gets the rights associated with it, and that ownership can change hands.

Each contract can, of course, change hands many times. Each time it changes hands, it's because the current holder would prefer to have money immediately instead of the contract that promises maybe some money in the future. Perhaps the investor wants to use that money to buy other stocks or bonds, or maybe they need it to pay for something completely outside the realm of finance.

Now there are two ways for investor #1 to get return: they can hold on to it to get dividends or coupon payments some time in the future, or they can sell the contract for more money than they paid for it for an immediate return. When people talk about the price of a share of stock or of a bond, what they mean is what someone else would be willing to pay for it today.

Going back to our Ford example, back in 2019 Ford stock was trading at about $9 per share. If you assumed that future dividends would also be $0.60, it would take 15 years ($9/$0.60 per year) of owning the stock for the dividends to make the return on the investment positive. Essentially if you owned one share of Ford in 2019, you might guess that you needed to hold it 15 years to make the investment worth holding on to.

Why would someone sell a stock or bond now if they'll eventually get dividends or coupon payments by holding on to it?

Remember that dividends and coupon payments are uncertain, and may happen sometime in the near or distant future. We guessed it would be $0.60 per year, but that was just that, a guess. It could be an informed guess, with big spreadsheets and evidence to back it up, but it's nevertheless a guess. Nobody can predict the future accurately.

In reality, Ford didn't provide any dividend in 2020. COVID was keeping people at home and the economic outlook was very uncertain. They only paid out $0.10 per share in 2021. Holding a stock brings risk!

However, the owner of a share of stock or the owner of a bond is able to sell to another investor when they want to, without permission from the corporation or government itself. That is, there is a market for the contracts, with buyers and sellers looking to unload or acquire the contracts for themselves.

By early 2022, Ford stock was selling for $24 per share, almost three times what it was going for in 2019. Someone who bought in 2019 and sold in 2022 would have had quite a return on their investment, though it was possible for it to go the other way entirely!

A quick aside on buying and selling bonds. Bonds return a fixed amount of money over time, regardless of what they trade for. If a bond is sold for more money to a second investor than the first paid for it, the return on that investment is going to be lower. More money in, same amount of money out.

Conversely, if a bond is sold for less money to a second investor than the first paid for it, the return is going to be higher. Less money in, same amount of money out.

Why might someone sell a bond? Well, if another bond has come out since the first one with a higher coupon, it could be tempting to sell the one you have and buy a new one.

That return on investment is known as the bond's yield. This is probably the trickiest bit of talking about bonds, even though it’s not that complicated, and likely why they don’t get as much clear press. If the price of a bond goes up, its coupon stays the same, which means that the yield goes down. Yield is the effective coupon rate, which is different if the bond has changed hands.

If the price of a bond goes down, again the coupon stays the same, so the yield goes up.

Just to be clear, if an investor bought a bond and never sold it, their yield would be the same as the coupon. In a world where bonds trade hands the yield and the coupon can diverge by quite a lot.

Exchanges

How is a price for these contracts actually set though? Does each investor need to talk to every other investor and personally ask them?

For rare kinds of contracts that aren't traded much, this is how it does work, but for stocks and bonds which are frequently traded, there is a middleman to make the process smoother: an exchange.

The exchange asks the current owner of a stock or bond, how much money they say they would sell for. It also takes bids from other investors for what they would be willing pay to own it. If the prices match, a deal is made and the contract changes hands.

Exchanges take the money and the contract, and settle everything within a few days. They make money primarily from corporations and governments paying a fee each year to let their stocks and bonds be traded in the exchange.

Corporations whose shares are traded on an exchange are called public corporations (or public companies), because anyone in the general public is able to buy and sell shares in those companies. Remember that Ford has about 4 billion shares outstanding, so if you buy 4,000 shares of Ford you get about one millionth of the dividends and one millionth of the say in who runs the company.

Corporations make money when they initially sell shares to the public, but after that the stock is trading among investors. They’re buying and selling stock that has already been issued. At that point, why do companies care about their stock price anyway? What does it even matter to a corporation if their stock is up or down? Do they care?

In the very short run, they don't, and you shouldn’t either. Short term stock fluctuations, like in the course of a few days or weeks, don't make much of a difference to a corporation. They don’t even make a difference to you if you own stock, and even less if you don’t. Over the longer term though, it does start to matter, for a few reasons.

First, remember who it is that chooses the CEO of the corporation: the investors. They own the company, and presumably they want to be able to resell their shares for more than they paid for them. If a corporation is doing things that cause their stock price to decline, investors might get nervous and want to make some changes. So it's in the interest of the CEO and other senior managers at the company to keep investors happy, which means a rising stock price. If investors who own 51% of the company decide to fire the CEO and replace them with someone else, they can.

Rising stock prices entice investors to invest more, making it easier for companies to raise money. If you did a Google search in the early 2000s, or took an Uber in the 2010s, you were benefitting from companies whose existence depended on happy investors willing to risk their money. There is a strange kind of subsidy from investors in early stage companies as they help bring corporations into existence that can give away products or charge low prices for some time, before reality eventually catches up and they need to actually make money from selling services or running ads.

Second, starting in the 1980s, lots of senior people at large public corporations started to get paid in a mix of salary and stock rather than salary alone. That means that they have a personal reason to want to bring their employer’s stock price up, separately from whether or not it's actually important to the company. If the stock price is high, they personally stand to make more money.

Third, if prices are high, companies can issue more stock! If a corporation wants to raise more money for something, instead of offering a loan, they can issue new stock. This is less common with large established corporations but it happens constantly for smaller ones.

A corporation can create new shares out of thin air, making each share worth a little less than before, since they’ve sliced their pie into more pieces. If before they had a million shares, and now they have 1.2 million, each share gets 20% less profit and each share grants 20% less control. The hope is that the new shares sell for enough that overall the value per share increases, though that doesn’t always happen.

What about bonds? Why should a corporation or government care if its bonds are resold? Why should you?

When a new bond is issued, the yields on the bonds that are being traded is a strong signal for what the new bonds will need to be priced at. A company or government whose bonds have gone up in price over time will generally be able to issue new bonds with a smaller coupon, since the risks are basically the same, meaning it costs them less to raise the money than it would have otherwise.

By contrast, if bond prices have fallen in the market, it means a corporation or government will need to issue new bonds with larger coupons in order to attract investors, costing the corporation or government more money in the long run. Falling bond prices means it will cost more to raise money.

This brings us to our final diagram explaining the various pieces of financial markets:

This process continues on indefinitely, until a corporation is entirely in private hands and doesn’t raise any more money from investors, or it goes out of business, or the government collapses, or capitalism ends.

Price changes

The particular prices for each share of stock is arbitrary, since what matters is the total value of the company and the amount of ownership per share. If a company decides to double (or triple) its number of shares (known as a stock split), each share will be worth half as much (or one third as much). Apple has split its stock five times since going public in the 1980s. Today their stock trades around $150 a share, but if it had never split each share would be worth $33,600!

Instead, the most important thing is how the price changes over time.

What about risk? How do we measure that? There's a lot of ways, but the most common is standard deviation, which is fancy way of saying how much the return varies on average each year.

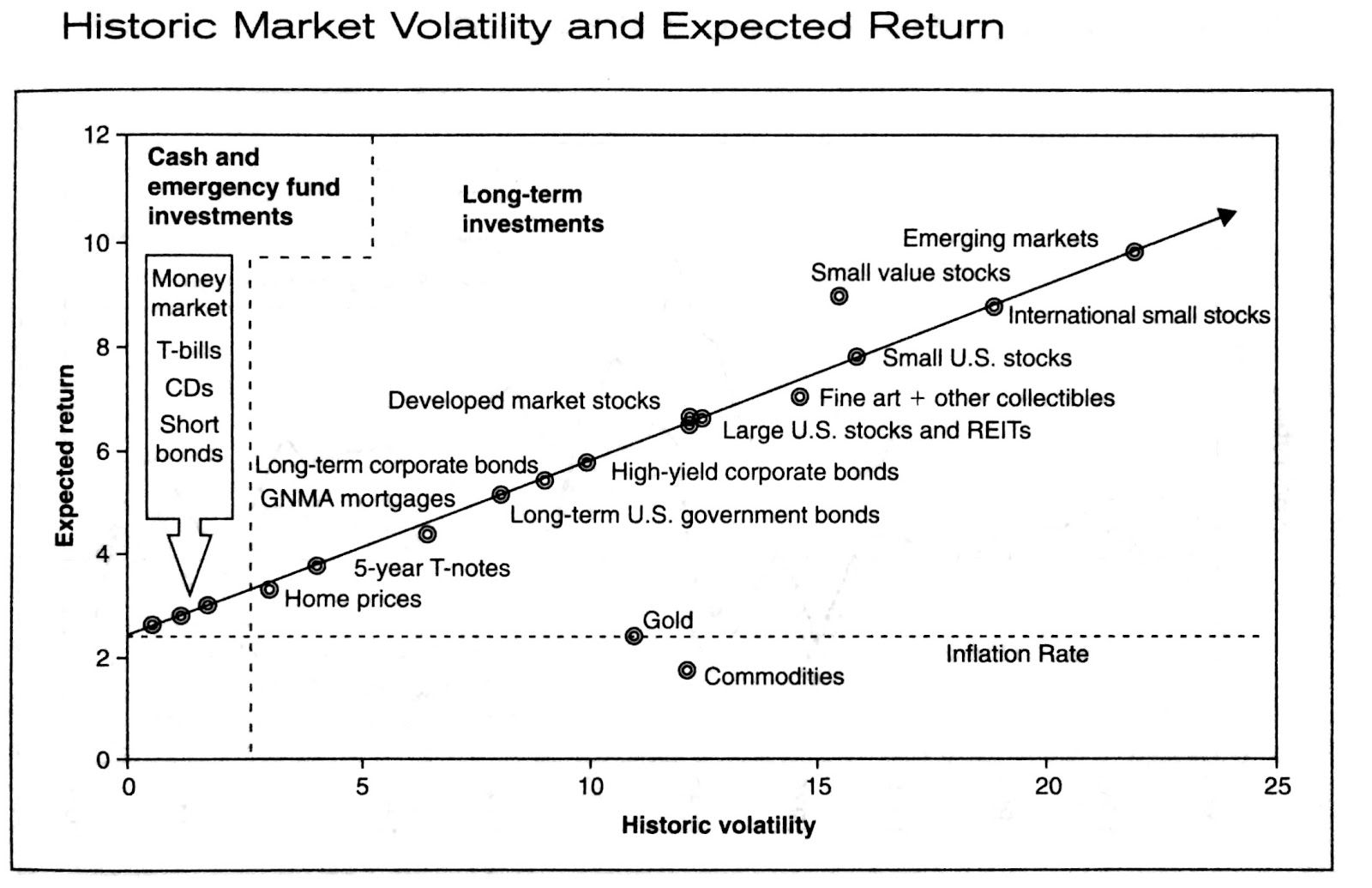

With all of this in place, we can get back to our earlier question of balancing risk and reward. Because most stocks and bonds are traded all the time, the market for them is fairly efficient. Markets are not perfect at judging prices, but generally speaking investors want to be compensated with more return when they are taking on more risk. And in fact, over a long time horizon, they do exactly that[4]:

In general, in an efficient market, as risk goes up, investors demand higher returns in order to accept that risk. And companies and governments don't want to give any more money away than they absolutely have to. That push and pull between is how prices are actually set.

Lower risk things are tied directly to good sources of money (governments which can raise taxes, corporate bonds which pay out regularly), and consequently are lower return. Higher risk things that are less likely to pay out (junk bonds, stocks with dividends) require more return average to justify the risk. Very high risk things (stocks for companies with no profit yet, governments in poor countries without much stability) have both the highest chance of paying out big and of going completely bust.

If you look at the chart, you see some outliers: gold and commodities (like oil, wheat, or iron). These are risky without generating average returns. The only way to make money on these is to be skilled and also lucky, and to trade frequently. There's no inherent reason to expect that their prices will continue to rise indefinitely.

Cryptocurrencies will more than likely fall into this same bucket over time, where the only way to make money is timing the market, which is another way of saying through luck.

Central banks and "the economy"

Let’s wrap up by pulling all of this together and discussing what people mean by “the economy,” how it relates to bonds and stocks, and and how it ties back to governments, and then revisiting our news stories.

Everyone in our society either works for a wage, or is supported by other people who work for wages. Children are supported by their parents. Wealthy people are supported by the profits on their investments, which are run by people who are paid wages. The elderly are supported by payroll and income taxes, which are collected when other people earn a paycheck. Everything in our system comes back to wage labor.

You could imagine a different world, and in fact our not-too-distant ancestors lived in one. When the majority of your country is engaged in farming (or hunting), wage labor is rare or exists as a sort of parallel world. I’m guessing if you’re reading this, that’s not your world today.

Because wages are so central to our society, there is pressure to keep them from growing too fast or too slow. The price of every thing and every service depends at least in part on the cost of the people you need to pay to make that thing or deliver those services. Not exclusively of course, since things still require raw materials and storage and everything else, but it’s an important factor.

General rises in prices are known as inflation. A small amount of inflation is good because it encourages people to spend money sooner (since in the future prices will be higher). A large amount of inflation is very bad because suddenly paying twice as much money for gas or food can leave people stranded or hungry.

Rises in wages are good for workers only if inflation rises less quickly than their wages. Wages go up when workers have a good bargaining position, usually because there are more jobs needed than people to fill them.

As a result, governments pay careful attention to the number of jobs being opened, and the percentage of people who want to work who are currently working, or unemployment. When unemployment is too high, governments want to make it easier for corporations to raise money and ultimately hire more people.

But make it too easy to hire people, and they risk inflation. Very low unemployment tends to mean that wages will rise quickly. If wages rise quickly and prices don’t rise as fast, it’s good. If wages rise quickly and prices rise even more quickly, you’re in a bit of a jam.

Now we come full circle back to the issue of central banks, first discussed in the section on sovereign bonds. Central banks like the Fed or the European Central Bank are responsible for raising money for their governments, but since the Great Depression they have most often used that responsibility to smooth out fluctuations that happen naturally in the business world. This is known as Keynesianism, after John Maynard Keynes, the visionary economist who first figured out that governments could be used for this between WWI and WWII.

The size and impartiality of a large government allows it to absorb higher borrowing costs (that is, a higher coupon) when it’s convenient, and that turns out be to quite useful. They do this by setting the coupon on short-term government bonds, known as setting the interest rate.

Central banks can set low interest rates for government bonds when they want, forcing investors to lend money to corporations in order to get a decent return, which stimulates economic activity. This pulls money out of the “real” economy, like a moth to a lightbulb. More money into corporations, more job open endings, higher wages, and possibly higher prices.

On the other hand, they can set higher interest rates too, pulling investment into government bonds and away from corporations, reducing economic activity. Higher interest rates take investor money out of circulation by parking it with the government, whose expenses don’t change that much from year to year. Corporations need to issue bonds with a higher coupon to raise money themselves, making less money available for productive uses. Stocks reduce in value because people can earn more money at lower risk by buying bonds.

In other words, central banks use these rates to control how much or how little economic activity is happening, which they use to try to balance out unemployment, wage growth, and price growth, and which has knock-on effects on the prices of stocks and bonds. It’s an extremely blunt instrument but it’s the one that we tend to rely on the most today.

Unfortunately, it takes months or even years to see the full impact of these decisions, so central banks are always trying to guess which way the wind is blowing and to set their dial accordingly. The slow feedback means that it’s particularly hard to get it right.

Since the 2008 financial crisis, central banks have had an additional tool in their toolkit: buying long-term bonds, or other long-term assets, directly from investors. In America this is known as Quantitative Easing, or QE. It’s hard to state how unprecedented this was when it started, even though it’s become normal now.

When a central bank buys billons of dollars of bonds, that drives bond prices up, since buyers have to compete with the central bank. Higher prices on bonds means lower yields, which means that new bonds can be issued with lower coupons, further stimulating the economy. This became necessary in some countries because the interest rates they were setting were already at zero percent! This practice is still fairly controversial, and we're still waiting to see what happens as central banks sell the assets they've bought.

Tying all of this back to our news stories

When people talk about "the stock market," they are usually referring to a collection of stocks together, which is known as an index. There are thousands of indexes out there, the most famous being the S&P 500. It tracks the 500 biggest companies in the US stock market. Two other big ones are the Dow Jones Industrial Average, which tracks 30 big industrial firms, and the Nasdaq composite, which tracks many technology stocks.

Prices of stocks from unrelated companies tend to move together, because they're driven by bigger things going on outside of the individual company, like interest rates, but also things like COVID or new technologies like the Internet.

Let's tie all of this together and get back to our two headlines we first looked at:

A "bear market" just means that the index has dropped more than 20% from a recent high. There's nothing magical about 20%, it's just a shorthand for a big drop.

So what this headline is saying is:

- An index of stocks has fallen at least 20% from a recent high

- It kept falling, meaning that the underlying stocks were being traded for less

- The Federal Reserve is going to make a decision in the near future about whether or not to raise interest rates, which might push down stock prices further

And let's look at our other example:

The ECB is the European Central Bank, which is roughly the European equivalent of the Federal Reserve.

What this headline is saying is:

- Prices of sovereign bonds for countries like Italy have fallen, which means that yields are up, which means that new Italian bonds will require a larger coupon, raising the cost to Italy to issue bonds

- The European Central Bank has a plan to buy bonds, like they did after the 2008 crash, which will presumably push their prices up

- Higher prices means lower yields, which means lower costs for countries in Europe to borrow

The additional bit of information to know here is that it's important to the Europeans that there is not such a big gap between bond coupons for Germany (who are considered as good an investment as the United States) and less financially stable countries like Italy, Greece, and Portugal. Having a big gap creates political problems, because of the way that the Eurozone is set up.

So there you go, after only 8500 words, hopefully you’ve got a better grasp on what the heck is going on in the news. Let me know if this was helpful, or useless, or too long, or any other thoughts, by shooting me an email (max at shron dot net).